|

| Design Principles of Emergency Response |

| All Crises Begin Locally |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| This lesson expands on the idea that all response to emergencies are bounded by space and time. On the one hand an emergency has a finite duration to which we must respond. By necessity, the earliest responses are limited by the inventory of local response assets and infrastructure. Response assets that are more distant take time to mobilize and deliver. |

| |

| Historically, the response to emergencies was the purview entirely of local authorities. With technological advances in transportation, communications, logistics and other technologies, an effective and efficient response through mutual assistance (local/state/federal) has become practical and valuable. However the roles and extent of the participation is governed by the division of powers in the state and federal constitutions. |

| |

| However the first responders to any emergency are the persons and assets closest to the site of the event or as emergency managers frequently remind us: ‘All Crises Begin Locally’.

|

| |

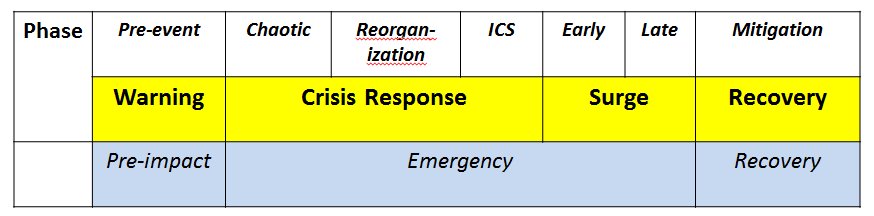

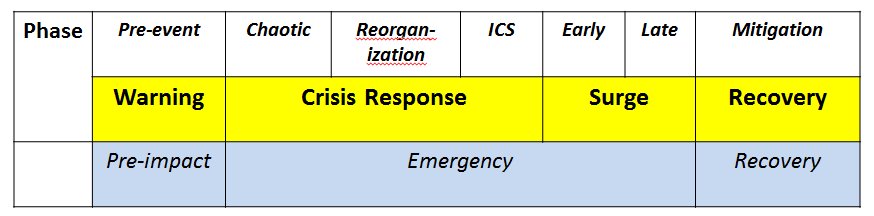

Phases of Disasters and Crises

Dynes, Quarantelli and Kreps 1981 have identified five phases of disasters and crises:

- Pre-disaster: everyday community life

- Pre-impact: earliest warning to impact

- Impact: disaster or crisis strikes.

Variable duration (tornado, flood, oil spill, etc.)

- Emergency: response to immediate demands

- Recovery: mitigation of effects and return to normal

Local Assets and Event Phases

|

| |

| Local Assets and Event Phases |

|

| |

Man-made or natural event recognized at onset

- Warning Phase: Threat Recognition

- Crisis Response Phase: LOCAL ASSETS

- Surge Phase: Mutual aid supplements local assets

- Recovery Phase: Return to normal

|

| |

Emergency management scenarios have limited geographic scope. Examples include:

- Individual medical emergencies

- Traffic and workplace accidents

- Fires (residential and industrial)

- Natural disasters (earthquakes, tornados, hurricanes, etc.)

- Environmental accidents

- Utility disasters (power grid, water, sewage, etc.)

- Food supply contamination

- Public health issues (Hepatitis, West Nile Virus, pandemic)

|

| |

Common features of these examples are:

- Initial management burden is local.

- Local and regional assets must be adequate for response

- Mitigation time may be critical (e.g., HAZMAT or fire control)

- State and Federal resources take time to engage

- Chain of command

- Transportation and Mobilization time

- Communications and transportation may be disrupted by crisis

|

| |

Effective response requires the engagement of local infrastructure including:

- Emergency Response Agencies

- Local Government

- Special District Governments

- Non-governmental organizations

- Red Cross, Faith-based organizations, not-for-profit

- institutions, neighborhood organizations, etc.

- Business sector (supply chain, etc.)

|

| |

In addition there is a need for "social engagement" of local social structures and trusted sources such as:

- Ethnic and racial communities

- Faith-based groups

- Primary self-identification groups

- Sexual orientation

- Age groupings

- Social networks (virtual, face-to-face, etc.)

|

| |

Examples of Local Crisis expansion to State and Federal Disaster Management

- Local resources are exceeded for a geographically constrained event

- San Francisco Earthquake of 1906

- Collapse of Minnesota I-35W bridge

- Geographically wide-spread event

- Hurricane Katrina

- BP Deepwater Horizon oil well

- Overlapping jurisdictions

- 9/11 Twin Towers and Pentagon attacks

|

| |

Preparedness and Emergency Response: Historical Development

- Local Response

- Major Fires

- Portsmouth, NH (1802), Detroit, MI (1805), Newburyport, MA (1811), Washington, DC (1812), Buffalo, NY (1813). Boston, MA (1824), New York, NY (1835), Pittsburgh, PA (1845), Nantucket, MA (1846), St. Louis, MO (1849), San Francisco, CA (1851), East Boston, MA (1861), Troy, NY (1862), Atlanta, GA (1864), Lawrence, MA (1864), Richmond, VA (1865), Kaiser Burnout, TX (1865), Portland, ME (1866), Port Huron, MI (1871), Chicago, IL (1871), Peshtigo, WI (1871), Boston, MA (1872), Thumb Fire, MI (1881), Martha's Vineyard, MA (1883), Charleston Earthquake, SC (1886), Seattle, WA (1889), Roxbury, MA (1894)

-

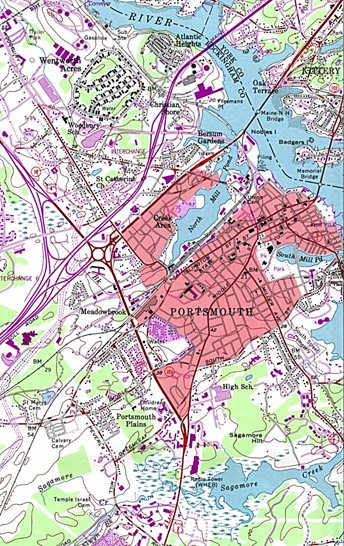

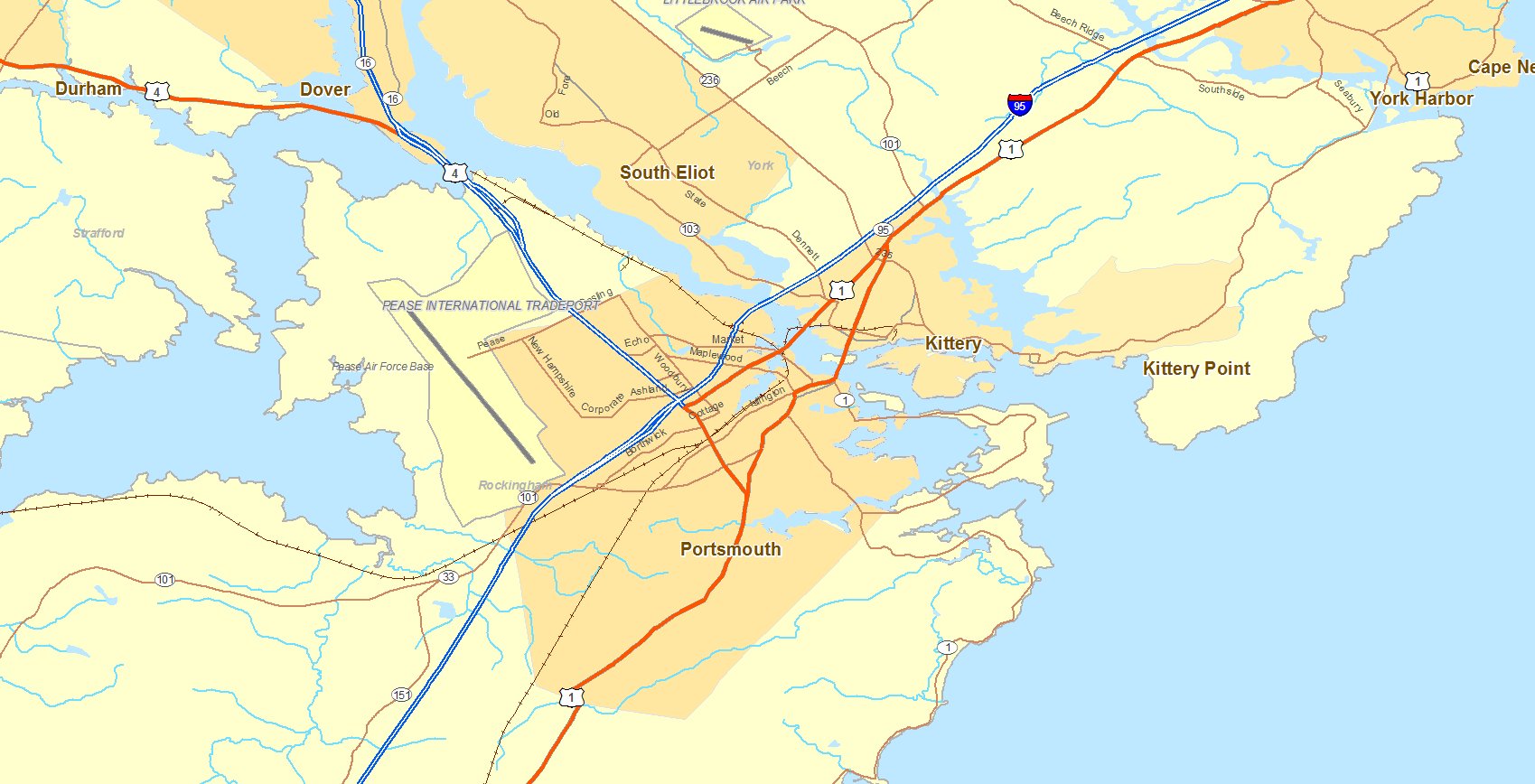

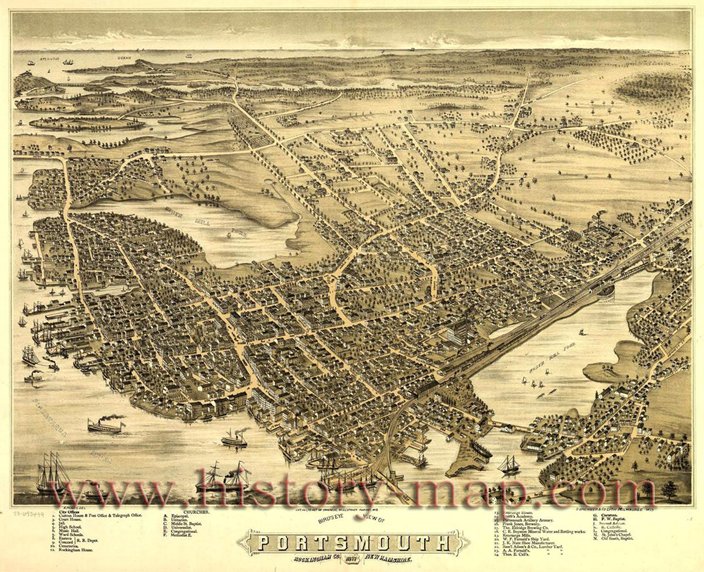

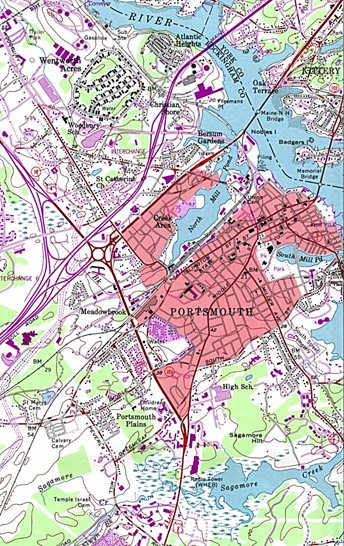

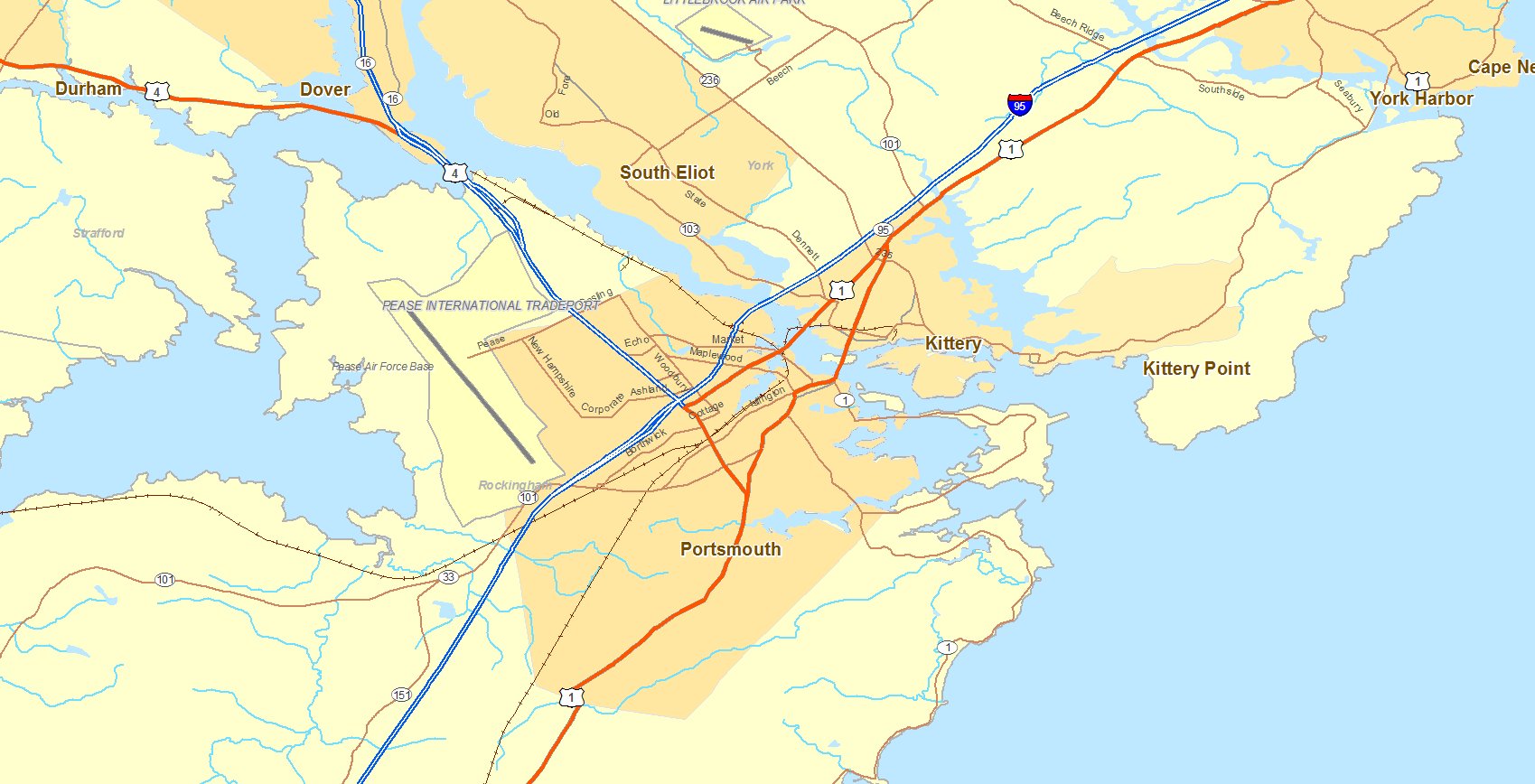

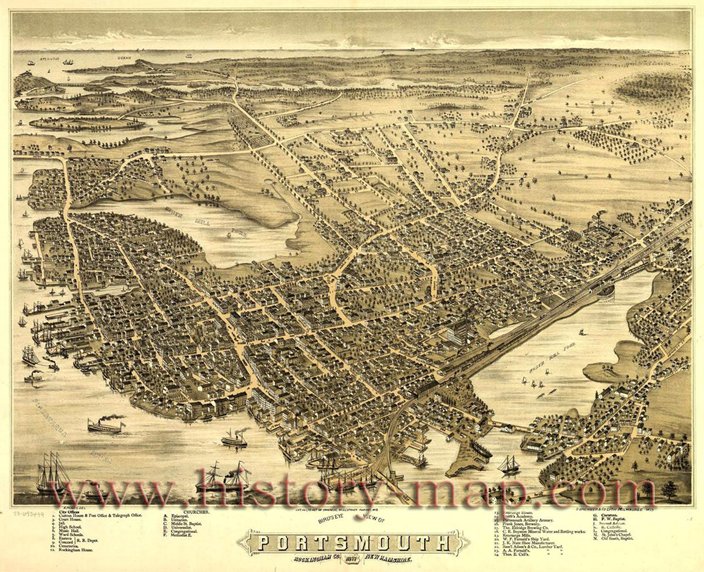

Portsmouth, NH Fires 1802, ’06 & ‘13

- Portsmouth, NH is major ice-free, deepwater port between Boston (60 mi south) and Portland ME (52 mi north) at mouth of Piscataqua River

- Major shipbuilding and mercantile center

- Rapid population growth for time: 4,720 people (1790) to 5,339 people (1800) to 6,934 people (1810)

- Portsmouth, NH Fires 1802, 1806 & 1813

- Portsmouth, today

- Portsmouth, NH Fires 1802, 1806 & 1813

- Construction: one- and two-story timber-frame structures linked by narrow dirt roads.

- Agrarian society: residents kept barns, stored hay,

- Lighting and heating technologies:

- candles and oil lamps

- Wood for cooking and heating

- Cooking grease in fireplaces with creosote-choked chimneys

- Portmouth, NH Fires 1802, 1806 & 1813

- Sunday December 26, 1802 at 4 am. Fire started on the site of the banking block in what is today Market Square and obliterated the city along Daniel Street. In the central "Parade" only the North Church and the Old State House were left standing.

- Damage was estimated then at $200,000 for the loss of nearly 200 buildings.

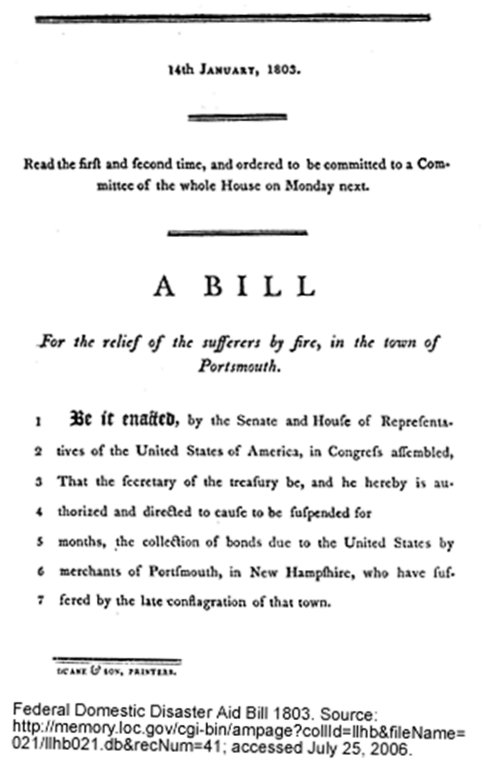

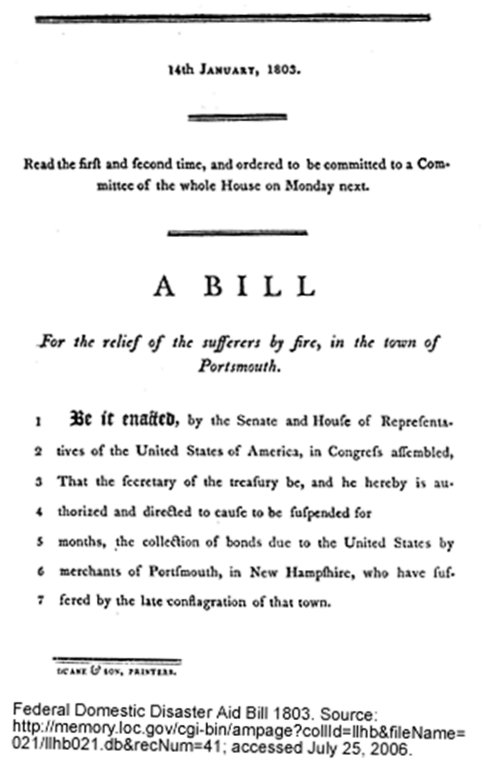

- Portsmouth, NH Fires Aftermath 1802

- Private contributions: ~$45,000

- January 14, 1803: Congress authorized suspension of bond collection from Portsmouth merchants

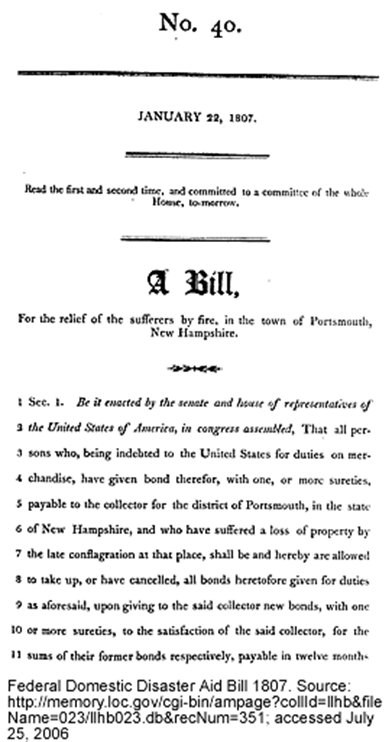

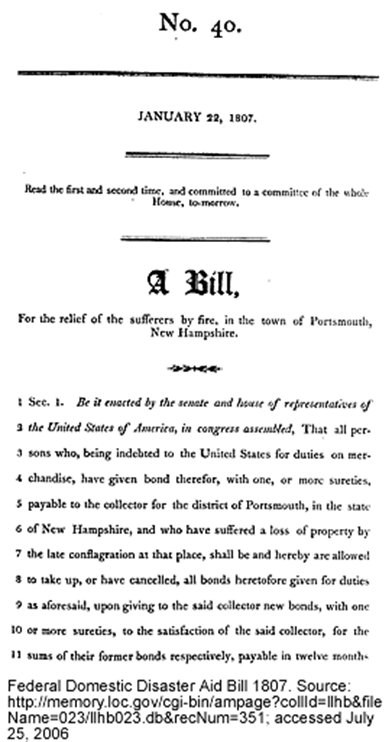

- Portmouth, NH Fires Aftermath 1807

- January 22, 1807 Act of Congress

- “all persons who, being indebted to the United States for duties on merchandise, have given bond therefore, with one, or more sureties, payable to the collector for the district of Portsmouth, in the state of New Hampshire, and who have suffered a loss of property by the late conflagration at that place, shall be and hereby are allowed to take up, or have cancelled, all bonds heretofore given for duties as aforesaid, upon giving to the said collector new bonds, with one or more sureties, to the satisfaction of the said collector, for the sums of their former bonds respectively, payable in twelve months.”

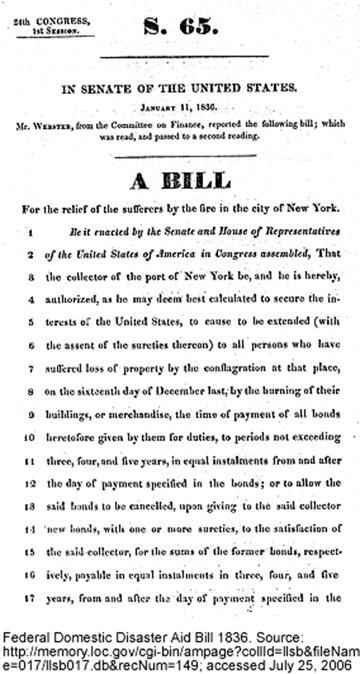

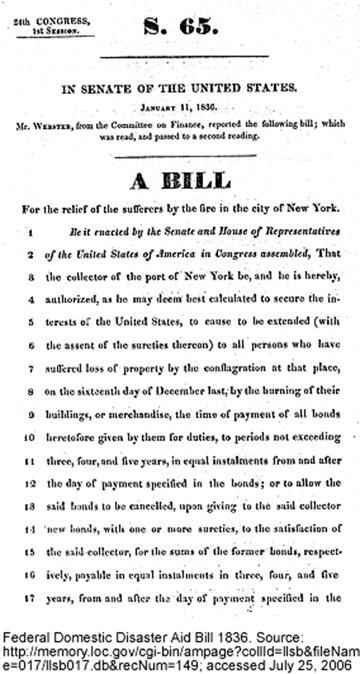

- New York Fire of 1835

- Congressional Relief: New York Fire of 1835

- “For the relief of the sufferers by the fire in the city of New York. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of American in Congress assembled, That the collector of the port of New York be, and he is hereby, authorized, as he may deem best calculated to secure the interests of the United States, to cause to be extended (with the assent of the sureties thereon) to all persons who have suffered loss of property by the conflagration at the place, on the sixteenth day of December last, by the burning of their buildings, or merchandise, …”

- Great Chicago Fire 1871

- Preparedness and Emergency Response: Historical Development

- Local response

- Natural disasters

- Johnstown Flood (1889)

- Galveston Hurricane (1900)

- San Francisco Earthquake (1906)

- Man-made disasters

- Mining accidents

- Industrial explosions—boilers, gas and explosives

- Transportation accidents

|

| |

San Francisco Earthquake 1906

Souvenir hunters at ruins of Stanford Mansion

|

| |

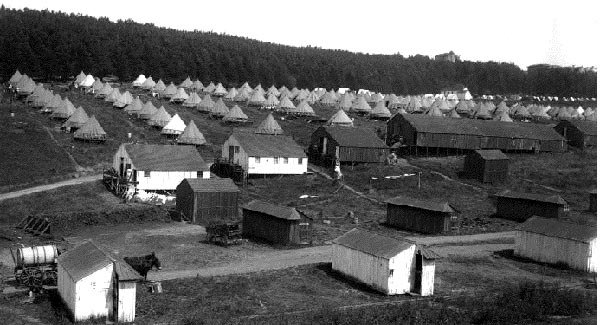

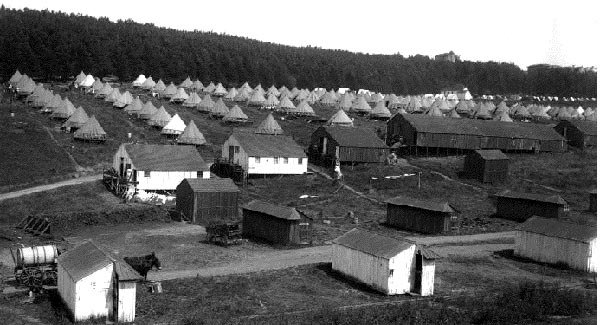

San Francisco Earthquake 1906

Shanty encampment near Marina before Army assistance (Before arrival of surge assets).

|

| |

San Francisco Earthquake 1906

Large refugee camp in Golden Gate Park. The large wooden building along the ridge top was Affiliated Colleges, now the site of the University of California Medical Center at Parnassus Heights.

|

| |

Evolution of Federal Involvement: Gradual Process

- Constitution: Federal and State Powers

- Tenth Amendment: reserves powers for the states if not specified in US Constitution

- Implied powers clause of the Constitution (Article 1, Section 8, Paragraph 18)

- Commerce Clause of Constitution (Article 1, Section 8, Paragraph 3)

- Extended to interstate navigation on waterways by Gibbons v. Ogden (22 U.S. 1, 1824)

|

| |

Evolution of Federal Involvement: Gradual Process

- EXAMPLE: Flood Control

- Initial responsibility local

- Rivers (and their flood plains) span multiple states

- Policy evolved in response to disasters (definition: event exceeded local response capability)

- Enabled by infrastructure advances

|

| |

Flood Control and Relief: Mississippi River

- Beginning 1727 in New Orleans: local levee construction

- 1824: Army Corps of Engineers authorized to remove some navigation obstructions

- Enabled Gibbons vs. Ogden (Supreme Court) decision extending Commerce Clause to river improvements

|

| |

Flood Control and Relief: Mississippi River

- 1849 and 1850: Swamp Lands Acts

- Transferred Federal “swamp and overflow lands” to states; revenue from sales designated for levees and drainage canals

- First “topographical and hydrographical survey”

- 1879: Congress creates Mississippi River Commission (major floods: 1862, 1865, 1869 and 1874)

- Survey river and tributaries

- Plan navigation and flood control

|

| |

Flood Control and Relief: Mississippi River

Great Flood of 1927: Arkansas City on Lower Mississippi

|

| |

Flood Control and Relief: Mississippi River

- 1917: Flood Control Act – lower Mississippi and Sacramento Rivers; levees-only approach

- Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 - Flood Control Act of 1928

- Abandoned levees only approach

- Introduced federal involvement in flood control

- Federal-state partnership

- Extension by later Congressional actions

|

| |

National Surge Assets: Examples

- Congressional Charter of American Red Cross of 1900

- Flood Control Acts of 1928 and 1936

- Civil Defense Act of 1950

- Federal Disaster Relief Act of 1950

- National Flood Insurance Act of 1968

- Disaster Relief Act of 1974

|

| |

|

| Copyright © 2011 - 2016 Carey Balaban |